Breaking the Resolution

Two machines on the internet can talk to each other iff both of them know each other’s IP addresses. When we type in “google.com” in the browser, the first task of the browser is to get the IP address of “google.com” which it does by communicating with the DNS system. Once an IP address is received, the browser establishes a TCP connection to the server, does a TLS handshake, exchanges data with the server before terminating the connection.

What would happen if the DNS system gives a bad IP for a domain? That is, rather than giving 172.217.164.206

for google.com, DNS answers with some other IP. How can that happen? Apart from a bug in the DNS resolvers,

there can be cases where a malicious user might eavesdrop for DNS queries from your system and replies back with

IP address over which she commands control and thereafter can snoop on the traffic from your machine.

To check out this scenario, let’s try to connect to google.com with an IP address of example.com such that

TCP and TLS handshake is done with example.com. There are multiple ways to do this: update your local

/private/etc/hosts to direct google.com to example.com, inject the bad RR in locally running DNS resolver

rrdns or much simpler, use curl’s --resolve option.

Let’s go with the 3rd option.

We can create a small HTTPS server using SSL certs signed by our own root CA using mkcert:

$ mkcert example.com

Using the local CA at "/Users/Karan/Library/Application Support/mkcert" ✨

Created a new certificate valid for the following names 📜

- "example.com"

The certificate is at "./example.com.pem" and the key at "./example.com-key.pem" ✅

Server code would execute the following line to run TLS server given SSL certificate and private key:

http.ListenAndServeTLS(":443",

"example.com.pem", // Certificate.

"example.com-key.pem", nil) // Private key.

Check if the server is running correctly:

curl \

--cacert rootCA.pem \ # Load the root cert from this path

--resolve example.com:443:127.0.0.1 \ # Use this mapping instead of asking DNS resolver

-vvv \

https://example.com

Now lets resolve google.com to 127.0.0.1 and hit our test server:

curl \

--cacert rootCA.pem \

--resolve \

google.com:443:127.0.0.1 \

-vvv \

https://google.com

which spits out

| |

We can see here that curl loaded its DNS cache with our entry, tries and succeeds to establish a TCP connection with localhost:443, loads the root certs from the custom path provided and then goes ahead to establish TLS 1.3 connection with the server, which fails because of no alternative certificate subject name matches target host name ‘google.com’.

What’s happening?

Every web server needs to prove its identity to the connecting client, failure of which would result in the client terminating the connection. The entity of proof is a digital certificate that a web server offers to the client, which on reception of cert runs multiple validations. Who certifies the server? Server gets its certification from Certificate Authority (CA), a third party neutral organization whose job is to verify that the server/org does own the domain for which it is asking the certificate for.

Server or domain administrator, generates a public/private RSA key pair and composes Certificate Signing Request (CSR) containing the public key and name of domains for which it intends to get a certificate for, signs it with the private key and sends it (CSR) to CA. CA verifies the CSR using the public key in it and also verifies if the domains for which the certificate is requested for, does actually belong to the requesting org/server/entity: earlier there used to be manual steps involved, like asking the domain controller to update DNS records temporarily which can assert the claim of ownership but lately the verification can be automated using ACME protocol by LetsEncrypt. Once verification succeeds, CA generates the X.509 certificate containing the public key of the requesting org, for how long the certificate is valid, identity of self as to who generated the certificate, list of domains this certificate is valid for in CN (Common Name) and SAN (Subject Alternate Name) fields and other various fields.

Note from the section above, the certificate is only valid for a selected list of domains. When client a made a

connection with the server, the server sent back its certificate to affirm its identity. Apart from many other

validations (like is the certificate signed by a verified CA, is the cert expired or not, etc) the client also

checks if the domain name to which it was trying to connect to matches the CN (Common Name) or SAN (Subject

Alternate Name) present in the certificate. This is the stuff that failed in our case as neither CN nor SAN in

certificate matches google.com. What are they in the certificate? CN is set to “mkcert

@.local ()” and SAN consists of DNS name=example.com and IP Address =

127.0.0.1. Both of these were set by the mkcert command for us.

Cool, so we now know why the failure occured. But what if we generate the certificate where SAN matches

google.com?

Lets generate cert for google.com: mkcert google.com, and load them into the server such that server looks

like this:

http.ListenAndServeTLS(":443",

"google.com.pem", // Certificate.

"google.com-key.pem", nil) // Private key.

and hitting the server with following curl request:

curl \

--cacert rootCA.pem \

--resolve google.com:443:127.0.0.1 \

-vvv \

https://google.com

outputs

| |

This is expected. The certificate does have google.com in it under SAN (subjectAltName) section which

matches domain present in the request.

One big advantage we have over an attacker is that we are able to inject CA’s root certificates into the client.

Note the “–cacert” option passed to curl which tells curl where to find the root CA certificate which was

used to issue X.509 cert to server. This ability is denied to attackers. Mostly clients come bundled with CA

certs and can also be provisioned to use CA certs installed in the system.

Is it possible for an attacker to use google.coms certificate as anyways it is public?

How can we get the SSL cert for google.com in PEM format??? Easy:

echo | openssl s_connect -showcerts -connect google.com.443 \

openssl x509 -out google.com-original.pem

This will create a file google.com-original.pem that will contain the digital certificate for google.com.

We can load this into our server, but there is a problem. We don’t have the private key. Note, at the time of

building CSR request we need to generate public/private key pair and the private key is used to sign the

request. In fact, if we can have the corresponding private key, Google’s existence is literally doomed.

This is a blocker but lets go forward and try to feed-in wrong private key to the Go server:

http.ListenAndServeTLS(":443",

"google.com-original.pem", // Certificate.

"bad-key.pem", nil) // Private key.

On running, the server fails with following error:

2020/08/24 17:42:44 ListenAndServe: tls: private key does not match public key

exit status 1

Of course! When the server loads the cert and private key, it generates corresponding public key from private key and matches it against the provided public key in first argument. This matching failed here, hence the error. Now we are certain that attacker cannot do any damage unless they have the private key corresponding to the public key.

If the imposter is somehow able to direct the browser to her IP which is backed by a webserver also controlled

by her, until the website is being accessed by HTTPS, she won’t be able to do any harm because the whole

certificate dance prevents her from faking the identity. But it is important to note that this only works if the

website is being accessed over HTTPS. In case the website is accessed over HTTP, there is no way for the

client to verify the identity of server it is communicating with and is easy for the attacker to fake its

identity. For example, she might direct scotiabank.com (a major bank in Canada) to her own malicious version

of the bank’s website and ignorant user won’t be able to differentiate and might end up giving private info to

the attacker, if the servers running the site were operating over HTTP.

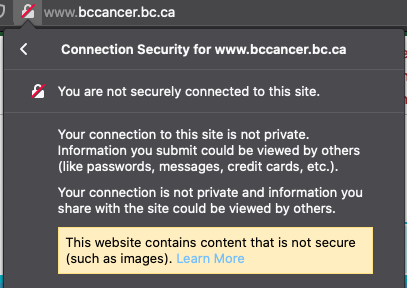

Though browsers are not unaware of such attack vectors and can take steps to inform the user about such

insecurity. For example, in Firefox, accessing a website over HTTP, http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/ (some sites

do a redirection from 80 -> 443) will result in indication on the url bar highlighting that communication with

website is insecure via a red mark on a lock. Though that is true enough to alert the user about the pitfalls

of using the website, the truth is, i can’t even verify if this website truly belongs to bccancer.bc.ca.

Another role browsers play is to enforce HTTPS on certain domains using something called HSTS policy mechanism.

It states that if when communicating with website W there comes a response with header containing HSTS (HTTP

Strict-Transport-Security) record then all future calls to W will be made over HTTPS until the duration

(max-age directive) specified in HSTS header. What about sub-domains like x.W or y.x.W? This is handled by

another valueless directive in the header named includeSubDomains that, quoting

RFC6797#6.1.2, “signals the UA [User Agent eg browser]

that the HSTS Policy applies to this HSTS Host as well as any subdomains of the host’s domain name.”

But then what would happen if the user is accessing the website W for the first time or when the HSTS policy has expired, because in that case HSTS policy won’t kick in as the browser has never communicated with W earlier or there is no valid HSTS policy in the browser? Lo and behold, all major browsers come up with a preloaded list of websites for which HSTS parameters have been submitted beforehand by the website owners. Request for removal or addition of domains can be made from here.

That gives a good idea that we’ll be reasonably secure if our browsers communicate with websites using HTTPS (specifically TLS1.3). But is it possible for someone to snoop encrypted traffic? Still do MITM?

Yes, iff the party doing MITM is able to create and inject its own CA in the user’s machine. And when does that happen? Welcome to corporate networks.

Lets say a corporation creates its own CA and installs the root cert in your system. Then if you go to

google.com on your browser, ClientHello message sent as part of TLS handshake will be intercepted by the

corporates proxy, a new certificate signed by its own CA root cert is created where CN/SAN is google.com, and

is sent back to the user in ServerHello message. As client has the corporate’s root certificate installed, its

verification of the presented certificate will pass. Once the TLS connection is established between user and

the proxy, proxy will establish a connection to the actual google.com server and forwards all traffic to it

after reading plaintext HTTP requests from the user. Not just the requests, but now the proxy can also read

the responses Compromised.

This is only possible if your computer can be controlled by an entity other than you. Otherwise, you’re safe.

Or, are we? Consider the case where there is no custom CA root certs present in your system and you always use HTTPS to communicate with websites. All traffic to the websites is encrypted, thanks to TLS, thereby no one in the middle can know the content of communication.

But there are few ways where an attacker can know which websites the user is accessing. Firstly, DNS queries are not encrypted. Attacker can figure out which websites you’re accessing by sniffing on DNS traffic originating from your machine or DNS traffic destined to your machine. This has been a problem for the industry for quite some time and current solution involves making DNS queries for HTTPS (DOH) or DNS over TLS (DOT). Using them, DNS queries will be resolved the same way content is fetched from any normal website over secure channel. Though for this to work the DNS resolver your machine is configured to contact must support DOH or DOT. Major public resolvers like Cloudflare, Google public DNS and Quad9 do provide DOT/H.

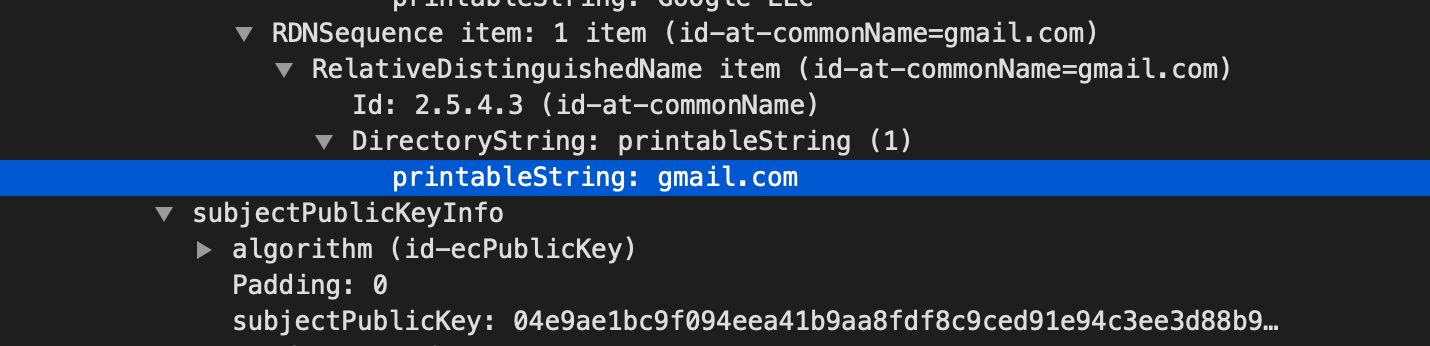

Secondly, as part of TLS handshake, server provides its certificate to the connecting client to assert its identity. The client can verify validity of the certificate to check if it is connecting to the correct server and not an imposter. In TLS1.2, the certificate sent by the server to the client is in plaintext. Note, as mentioned above, the certificate includes name of the website to which the client is trying to connect hence creating a hole which can be exploited by the attacker. This is how it looks like in wireshark (note, i’m not using SSLKEYLOGFILE to help wireshark decrypt TLS traffic):

Good news is that this got fixed in TLS1.3 The certificate sent by the server is encrypted using symmetric key generated by the client and server using Diffie–Hellman key exchange.

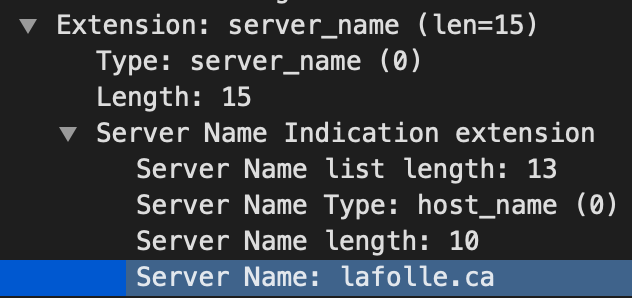

Thirdly, the ClientHello message sent by the client to the server to establish TLS connection contains in

plain sight the name of the server it intends to connect talk. This field is call SNI - Server Name Indication.

In old days a single IP used to host a single HTTPS site thereby serving a single SSL certificate. As the world

evolved, this was not the case any more - a single IP could be used to host multiple domain names. For

example, consider the case of this website- lafolle.ca. On digging it we get:

$ dig +short lafolle.ca

104.248.60.43

162.243.166.170

which correspond to IP addresses at which Netlify is listening for TLS connections. In fact, Netlify is not

just listening for connections for lafolle.ca. Had that been the case it would have been extremely

inefficient as that would require dedicated IP for each website it hosts. Rather, it listens for all HTTPS

traffic at these addresses. But then how would it know which site (SSL certificate) to serve? You guessed it

right. Using SNI field in ClientHello message. As soon as it gets a ClientHello, it checks the SNI field of

the ClientHello to determine which site it should offer. In this case it would be lafolle.ca as seen in

wireshark:

SNI field is sent unencrypted to the server because at

this point in TLS handshake no symmetric key has been established yet. Though, it is established by the time

server sends SSL certificate to the client.

SNI field is sent unencrypted to the server because at

this point in TLS handshake no symmetric key has been established yet. Though, it is established by the time

server sends SSL certificate to the client.

This is where ESNI, Encrypted Server Name Indication, is born. The problem here is that at the time of establishing a connection the client does not know anything about the server. There is no symmetric key present which can be used to encrypt the SNI. Only after the initial stage of TLS handshake, is the shared secret key negotiated (using DH in TLS1.3). If that is the case then what can be used to encrypt the SNI? In ESNI, the SNI is encrypted using public key of the provider that hosts the domain to which TLS connection is being established. And how does the client get to know about the public key associated with the domain? DNS.

The owner of the domain publishes its public key in DNS record which the client extracts before rolling out the connection. Once fetched, the client uses that (server’s) public key and some random data generated by self to create a secret key, encrypts the SNI and sends it along with its own (client’s) public key to the server.

At the other side, the server extracts the public key from ClientHello, creates some random stuff and generates the symmetric key. That’s Diffie Hellman in action. Using this key the server decrypts the ESNI present in the message and serves the host to which it points to.

Lastly, imposters can read the src/dst IP address of TCP packets to know which sites are being accessed. I don’t think there is yet a way to fix this.

Conclusion

Always use HTTPS (with TLS1.3) and at the server side, keep good care of your private keys to protect yourself as well your customers from malicious entities.